Your cart is currently empty!

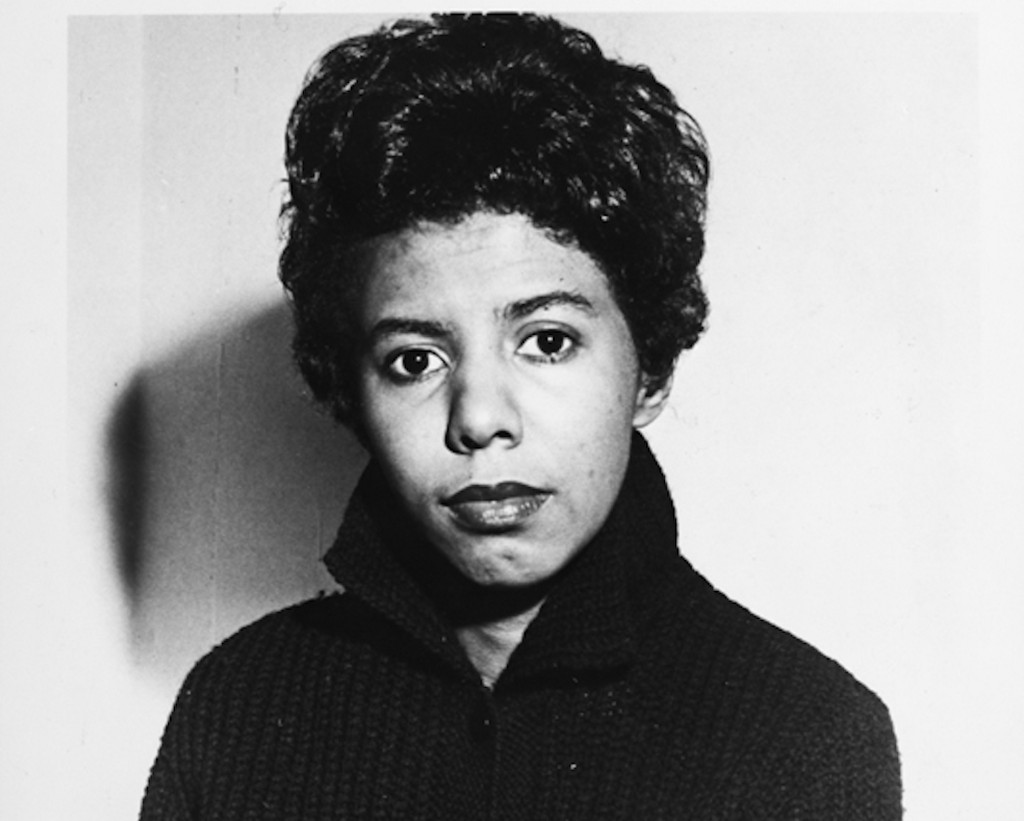

Lorraine Hansberry

Born: May 19, 1930

Birthplace: Chicago, Illinois, United States

Death: January 12, 1965

Gender Identity: Cisgender Woman

Pronouns: She/Her

Sexual Orientation: Lesbian

Nationality: American

Ethnicity: African American

Profession: Playwright, Author, Activist

Years Active: 1950–1965

Genres: Drama, Political Essay, Civil Rights

Associated Authors: Robert Nemiroff, Paul Robeson, James Baldwin, W.E.B. Du Bois

Overview

Lorraine Vivian Hansberry was a playwright, essayist, activist, and cultural icon whose play A Raisin in the Sun made her the first Black woman to have a show produced on Broadway. She was also the youngest American and the first Black playwright to win the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award. An outspoken lesbian, a committed radical, and a visionary writer, Hansberry’s life and work reflected deep intersections of race, gender, class, sexuality, and anti-colonial solidarity. She died at just 34 of pancreatic cancer, leaving behind a legacy that reshaped American theater and inspired future generations.

Early Life and Family

Born at Provident Hospital on the South Side of Chicago, Lorraine was the youngest of four children. Her father, Carl Augustus Hansberry, was a successful real estate broker and founder of one of Chicago’s first Black-owned banks. Her mother, Nannie Louise Perry Hansberry, was a schoolteacher and ward committeewoman. Her uncle William Leo Hansberry was a noted African studies scholar at Howard University.

In 1937, the Hansberrys moved into a white neighborhood in defiance of racially restrictive covenants. A mob gathered, and a brick thrown through a window narrowly missed eight-year-old Lorraine. Her mother reportedly guarded the home with a German Luger pistol. The legal case that followed, Hansberry v. Lee (1940), reached the Supreme Court and marked a turning point in the battle against housing segregation.

Their home regularly hosted prominent Black figures, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Duke Ellington, and Jesse Owens. These early experiences steeped Lorraine in political consciousness, Black cultural excellence, and a sense of justice.

Education and Political Development

Hansberry graduated from Englewood High School in 1948 and enrolled at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She initially studied painting but switched to writing and activism, joining the Communist Party USA and integrating a dorm. She also worked on Henry Wallace’s 1948 presidential campaign.

She later studied at the Art Institute of Chicago, Roosevelt University, and the New School for Social Research in New York. While in New York, she joined Paul Robeson’s newspaper Freedom and worked with W.E.B. Du Bois. Hansberry became deeply involved in global anti-colonial struggles, writing in support of Kenya’s Mau Mau uprising and critiquing Western imperialism. She also attended the 1952 Peace Conference in Uruguay.

Marriage and Queer Identity

Hansberry married Jewish songwriter Robert Nemiroff in 1953. They met at an anti-discrimination protest. Though they divorced in 1962, Nemiroff remained her closest collaborator and literary executor. She identified as a lesbian and contributed to The Ladder, the Daughters of Bilitis magazine, under the initials L.H. She built friendships with LGBTQ+ peers, took lovers, and subscribed to homophile literature. In her journals, she vowed to stop hiding and embrace her identity. Her queerness, hidden from public view during her life, was central to her personal evolution and posthumous legacy.

Literary Work and Theatre Career

Hansberry began work on her first play, The Crystal Stair, inspired by Langston Hughes’ poem “Mother to Son.” Renamed A Raisin in the Sun, the play opened at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre on March 11, 1959. It ran for 530 performances and earned four Tony Award nominations. Directed by Lloyd Richards, it became the first play by a Black woman on Broadway and marked the first time many Black Americans saw their lives reflected on stage.

A Raisin in the Sun was adapted into a film in 1961 starring Sidney Poitier. Hansberry became the first Black winner of the New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award and, at 29, its youngest.

Her second play, The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window, drew on her experiences in Greenwich Village and opened in 1964. It closed the day she died in 1965 after 101 performances. Other works include Les Blancs, The Drinking Gourd, What Use Are Flowers?, and Toussaint, most completed posthumously by Nemiroff. Her unfinished novel and essays reveal a wide scope of thought, ranging from anticolonial revolution to post-apocalyptic humanism.

Civil Rights and Radicalism

Hansberry was a fierce advocate for civil rights, socialism, feminism, and anti-imperialism. She criticized respectability politics and called for militant, multifaceted resistance. In 1963, she joined a group of Black artists including James Baldwin to confront Attorney General Robert Kennedy. Hansberry famously walked out in frustration, demanding moral clarity over political calculation.

She spoke at the historic 1964 Town Hall forum The Black Revolution and the White Backlash, calling for white liberals to become radicals and support full systemic change. Despite battling cancer, she continued to speak out. Her writings explored existentialism, Black atheism, antiwar activism, and the failures of American democracy.

Hansberry emphasized the need for transformation, not accommodation. “We must concern ourselves with every single means of struggle: legal, illegal, passive, active, violent and non-violent,” she once wrote. “They must harass, debate, petition… and shoot from their windows when the racists come cruising through.”

Death and Legacy

Hansberry died of pancreatic cancer on January 12, 1965, at age 34. Her funeral drew hundreds, with tributes from Paul Robeson, James Baldwin, and Martin Luther King Jr.

Her ex-husband Robert Nemiroff completed Les Blancs and adapted her writings into To Be Young, Gifted and Black, which premiered off-Broadway in 1969 and later became a book and a title for Nina Simone’s iconic anthem.

Hansberry’s legacy includes revivals of Raisin, a Tony-winning musical adaptation, and the 2018 PBS documentary Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame, Legacy Walk, American Theatre Hall of Fame, and Chicago Literary Hall of Fame. Her life is the subject of multiple biographies, including Looking for Lorraine by Imani Perry.

In 2022, a statue of Hansberry titled To Sit A While by Alison Saar was unveiled in Times Square and later moved to Navy Pier in Chicago. It features Hansberry surrounded by five symbolic chairs, each representing a facet of her legacy.

Major Works

- A Raisin in the Sun (1959)

- A Raisin in the Sun, screenplay (1961)

- The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window (1964)

- Les Blancs (1970, posthumous)

- To Be Young, Gifted and Black (1969)

- The Drinking Gourd, What Use Are Flowers?, Toussaint (unfinished)

- The Movement: Documentary of a Struggle for Equality (1964)

- Essay: “On Summer”

Queer Significance

Lorraine Hansberry lived her truth quietly but powerfully. Through her letters, journals, and legacy, we now understand her as a pivotal Black lesbian figure. She called out sexism in both gay and straight spaces, advocated for women’s equality, and helped lay the groundwork for intersectional queer theory. She saw queerness as inseparable from the fight for liberation.

Honors and Tributes

- New York Drama Critics’ Circle Award

- Tony nominations and Broadway revivals

- Nina Simone’s To Be Young, Gifted and Black

- Inducted into: Chicago Gay and Lesbian Hall of Fame, Legacy Walk, National Women’s Hall of Fame, American Theatre Hall of Fame

- Statue: To Sit A While by Alison Saar

- Subject of Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, Looking for Lorraine, and academic studies

- Namesake of schools, theaters, dormitories, and artistic projects nationwide

Rest in Power, Lorraine Hansberry.

Sources Cited

- Imani Perry, Looking for Lorraine: The Radiant and Radical Life of Lorraine Hansberry (Beacon Press, 2018)

- Sighted Eyes/Feeling Heart, dir. Tracy Heather Strain, PBS American Masters (2018)

- Patricia and Fredrick McKissack, Young, Black, and Determined: A Biography of Lorraine Hansberry (Holiday House, 1998)

- Emma Z. Rothberg, “Lorraine Hansberry,” National Women’s History Museum (2022), womenshistory.org

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Lorraine Hansberry,” updated by René Ostberg (2025)

- NPR Code Switch, Karen Grigsby Bates, “Lorraine Hansberry: Radiant, Radical—And More Than ‘Raisin’” (2018)

- Chicago Public Library, “Lorraine Hansberry Biography”

- James Baldwin, Sweet Lorraine, in To Be Young, Gifted and Black (Vintage Books, 1995)

- Kevin J. Mumford, Not Straight, Not White: Black Gay Men from the March on Washington to the AIDS Crisis (University of North Carolina Press, 2016)

- Cheryl Higashida, Black Internationalist Feminism (University of Illinois Press, 2011)

- MELUS Journal, Stephen R. Carter, “Commitment amid Complexity: Lorraine Hansberry’s Life in Action” (1980)

- Radical History Review, Fanon Che Wilkins, “Beyond Bandung” (2006)

Leave a Reply