Your cart is currently empty!

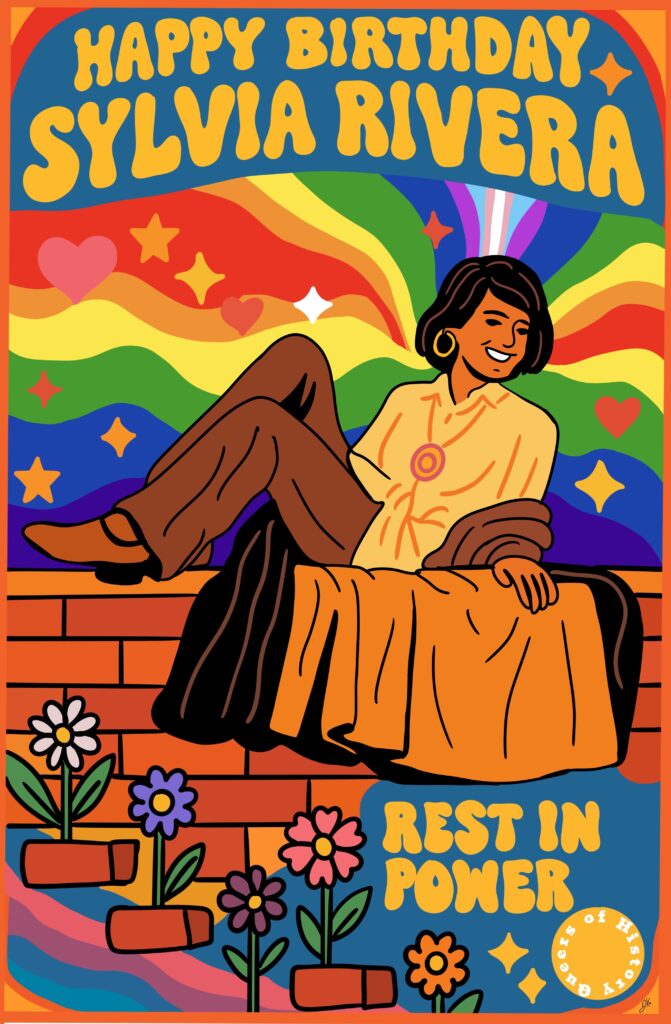

The Sylvia Rivera You Might Not Know

In honor of her birthday — July 2

Sylvia Rivera is often remembered as one of the first to rise up during the Stonewall uprising in 1969. She is called a pioneer, a hero, and a symbol of trans resistance. And she was all of those things. But if all we know about Sylvia is that one night at a bar, then we are missing the full picture of who she was and what she gave to the movement.

Sylvia’s life did not begin or end at Stonewall. Her story stretches far beyond a single act of defiance. She spent her entire life fighting for those pushed to the margins. She was a Latina trans woman who grew up on the streets, survived violence and homelessness, and never stopped calling out the failures of the movement she helped start.

She was angry, kind, exhausted, relentless, loyal, loud, and deeply human. She was not perfect, and she never tried to be. She was someone who lived the truth of what it meant to be queer, poor, and unwanted by the systems that claimed to fight for justice.

Sylvia Rivera was not just a historical figure. She was a person who showed up, even when no one wanted her there. She told the truth, even when it made people uncomfortable. She cared for others, even when she had nothing. She demanded liberation that included all of us, not just the ones who fit into neat boxes.

The stories below are not always easy. They are not polished or sanitized. They are not the kind of stories that usually get turned into speeches or documentaries. But they are real. And they are important.

This is the Sylvia Rivera you might not know.

1. She Was Kicked Out of the Human Rights Campaign Office

In the early 2000s, Sylvia Rivera walked into the New York City office of the Human Rights Campaign and demanded answers. She was angry, and rightfully so. For years, national and statewide LGBTQ organizations like HRC and the Empire State Pride Agenda had built political strategies that intentionally left out transgender people. They were backing legislation such as the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA) in New York and the federal Employment Non-Discrimination Act (ENDA), both of which originally excluded protections for gender identity. Sylvia saw this as yet another betrayal in a long pattern of trans erasure, especially by those claiming to speak for the whole community.

That day, Sylvia confronted HRC staff directly. She shouted, “You’re fucking with my people’s lives,” as she was physically removed from the building. Sylvia did not come with press or a crew. She came because she was furious. She came to make sure they knew that trans people were not going to quietly wait to be included when it was convenient.

This moment is not widely documented in video or photo form, but it has lived on through eyewitness accounts, activist circles, and Sylvia’s own retelling. It was one of many acts of resistance she carried out near the end of her life. Even as her health was failing, she continued fighting the white, cis, upper-middle-class establishment that had grown comfortable leaving trans people behind.

What came after her protest was a slow shift. The broader movement began to reckon more publicly with how trans people had been sidelined. HRC eventually shifted its stance and supported a fully trans-inclusive ENDA, although it took years of pressure from activists across the country. Sylvia did not live to see many of those changes fully take shape, but her refusal to stay silent helped pave the way.

Her confrontation at HRC was not just a tantrum. It was a deeply personal act of protest from someone who had lost too many friends, been homeless too many nights, and watched too many trans people be cast aside for the sake of political convenience. Sylvia went to HRC that day because she believed every trans life mattered, even if the mainstream movement did not.

2. She Was Silenced by Her Own Movement

After the Stonewall uprising, Sylvia Rivera helped build the foundations of the modern queer liberation movement. She worked alongside groups like the Gay Liberation Front and later the Gay Activists Alliance. She fought for housing, for legal rights, for safety. But as the movement gained visibility and political traction, Sylvia found herself pushed aside by the very people she had fought for.

Sylvia was told, again and again, that she was too loud. Too messy. Too angry. Trans issues were considered “too controversial,” and her presence at organizing meetings was increasingly unwelcome. She was told not to speak at rallies unless she avoided talking about being trans or poor. In some cases, she was not allowed to speak at all.

By 1973, Sylvia had reached her breaking point. At the Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally, one of the earliest Pride events, she forced her way onto the stage after organizers tried to keep her out. What followed was her now-legendary “Y’all Better Quiet Down” speech. Her voice shook with emotion as she addressed a crowd that did not want to hear from her. She reminded them that she had been beaten, arrested, and nearly killed in the struggle for queer rights. She asked how they could talk about liberation while abandoning those who had been on the front lines from the beginning.

The crowd booed her. Some threw bottles and trash. People who had once marched beside her now turned their backs. But she finished her speech anyway. Sylvia was not there to win popularity. She was there to tell the truth.

This moment marked a shift in her relationship with mainstream queer organizations. She continued her work on the streets, forming STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries) with Marsha P. Johnson, and focusing on supporting trans youth, sex workers, and homeless queers. But she never forgot how quickly the movement she helped build had tried to erase her.

Sylvia’s experience serves as a reminder that not all silencing comes from outside forces. Sometimes the erasure happens from within. Respectability politics and strategic compromise often come at the cost of the most vulnerable. Sylvia knew that. She lived that. And she never stopped calling it out.

3. She Lived Under a Highway

After years of activism, organizing, and fighting for other people’s safety, Sylvia Rivera found herself without a place to live. During the 1980s and 1990s, as queer organizations became more professionalized and politically focused, Sylvia was left behind. She had no steady income, no institutional support, and no permanent housing. For a time, she lived in a tent under the West Side Highway in New York City.

She stayed near the Hudson River, where she had spent much of her early life. Despite the harsh conditions, she never gave up on the community. Even while living outdoors, Sylvia continued to help others. She offered guidance to young trans girls who were also living on the street. She gave them advice, protection, and whatever small resources she could manage. In many ways, her tent became a kind of informal shelter, just like STAR House had been in the early 1970s.

This period of her life is often ignored in mainstream accounts, perhaps because it does not fit the polished narrative people want to tell. But Sylvia herself spoke openly about it. She was angry but not defeated. She knew what it felt like to be celebrated one moment and discarded the next.

When she re-emerged into activist circles in the late 1990s and early 2000s, she did not hide the fact that she had been homeless. She called out the gay and lesbian organizations that had allowed someone like her to fall through the cracks. She made it clear that housing, survival, and dignity were not optional. They were core parts of queer liberation.

Sylvia’s time under the highway was not a moment of failure. It was a continuation of her fight. She had always lived on the edge of society. She had always done her best work there.

4. She Fought to Keep the “T” in LGBT

By the mid-1990s, Sylvia Rivera had watched the mainstream gay rights movement drift further and further away from the people it claimed to represent. Trans people, especially those who were poor, of color, or doing street work, were being left out of policies, bills, and even Pride events. For Sylvia, this was not just frustrating. It was a deep betrayal.

In 1994, New York passed the Sexual Orientation Non-Discrimination Act (SONDA), but only after removing protections for gender identity. Sylvia and other trans activists had pushed to be included, but the bill’s backers said they had to make it more “passable” for lawmakers. That logic was not new. Sylvia had heard it for decades. Trans people were always told to wait their turn, to keep quiet, to not make things harder.

She refused.

Sylvia began confronting organizations directly. She showed up at Pride events holding handmade protest signs. She interrupted speakers to call out trans exclusion. She spoke to crowds that did not want to hear her. In one instance, she walked up to the front of a Pride stage and yelled, “You don’t want trans people at your table, but you’re happy to sit on our backs.” Organizers often tried to shut her down or pretend she was just being disruptive. But she was telling the truth.

For Sylvia, this was not about political correctness. It was about survival. She had seen firsthand what happened to trans people who were denied housing, health care, legal protection, and safety. She had buried too many friends and watched too many others vanish without a trace.

She made it her mission to keep trans people visible and accounted for, even if it meant being labeled a troublemaker. She helped lay the groundwork for future trans advocacy by refusing to let the “T” be an afterthought.

Sylvia believed that a movement that left out the most vulnerable was not a movement worth celebrating. And she made sure no one could forget that.

5. Her Latinx Identity Was Erased Too

Sylvia Rivera was Puerto Rican and Venezuelan. She spoke Spanish fluently, grew up in a Latinx household, and navigated the world as a brown-skinned child in 1950s and 1960s New York. Her culture shaped everything about her. But as she got older and deeper into the queer liberation movement, she found that white activists often erased that part of her.

In gay spaces, her accent was mocked. She was told to “speak better” or “clean up” her appearance. Some organizations highlighted her identity as trans when it was useful but rarely acknowledged her as a Latina. Sylvia herself talked about this, saying she often felt invisible in white-led queer spaces, even when she was standing at the front of the movement.

She also noticed how racism played out in whose lives were valued. White gay men with money were often the focus of legal campaigns and community support, while Black and brown queer people, especially trans folks, were left to fend for themselves. Sylvia saw how the system treated her differently. She had been arrested, homeless, harassed, and ignored. But when she tried to talk about racism in the queer community, she was often told to quiet down or focus on “unity.”

She never stayed quiet.

Sylvia’s Latinx identity was central to how she saw the world. It informed her belief in collective care, her resistance to police, and her connection to street survival. She called out white supremacy inside the LGBTQ movement long before it was common to do so. She pushed for more inclusive conversations around race, class, and immigration, even when people rolled their eyes or walked away.

The truth is, Sylvia was not just a trans trailblazer. She was also a proud Latina who carried her heritage into every protest, every speech, every act of care. Erasing that part of her is a disservice to her legacy.

We cannot understand Sylvia Rivera without understanding the racism she fought. Her voice mattered because it came from the intersections of so many struggles. And she never let anyone forget that.

6. She Nearly Ended Her Life After Being Forgotten

By the 1990s, Sylvia Rivera had been pushed to the edges of the very movement she helped create. Once a visible force in queer activism, she was now treated as an outsider. Mainstream LGBTQ organizations no longer invited her to events. Trans people were being written out of legislation. Poor, unhoused, and gender-nonconforming folks were ignored or deliberately excluded. Sylvia felt abandoned.

She was grieving. In 1992, her closest friend and comrade, Marsha P. Johnson, had been found dead in the Hudson River. Police quickly ruled it a suicide, but Sylvia believed Marsha had been murdered. The pain of that loss, combined with years of systemic neglect, wore her down. She had lived through beatings, homelessness, and constant rejection. But this new kind of silence was harder to survive. Being erased by her own community cut deeper than anything else she had endured.

One day, Sylvia walked to the river where Marsha had died and tried to follow her. She entered the water intending to end her life. But in that moment, Sylvia later said, she felt Marsha’s presence. She felt pulled back. She chose to keep living.

That decision marked a turning point. Sylvia got sober. She slowly reentered activism, this time with a sharpened focus. She began working with younger trans activists and community groups. She spoke publicly again, telling the truth about how trans people were being left behind. She did not hold back. She reminded everyone that the queer movement could not call itself liberated while trans people continued to die on the streets.

She became involved in early organizing efforts that would lead to the founding of the Sylvia Rivera Law Project. Her voice helped shape the direction of trans advocacy in New York and beyond. She used her experiences to demand real, material change for others who were still struggling.

Sylvia did not just survive that moment at the river. She returned stronger and more defiant. She reminded the world that queer history is not always a clean narrative of progress. It is also a story of loss, survival, and choosing to live when everything tells you not to.

7. She Never Gave Up on Marsha

Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera were more than just friends. They were chosen family. They stood beside each other through police raids, homelessness, poverty, and protest. Together they founded STAR (Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries), created safe spaces for trans youth, and helped shape the early queer liberation movement. Even when they disagreed or drifted apart, their bond never broke.

In 1992, Marsha’s body was found floating in the Hudson River, near the Christopher Street piers where both she and Sylvia had spent so much of their lives. The NYPD ruled her death a suicide almost immediately, despite witness accounts that suggested otherwise. People reported seeing Marsha being harassed near the water shortly before her death. Some believed she had been attacked or pushed. The police closed the case quickly, showing little interest in investigating further.

Sylvia did not accept the official story. She was devastated, but also furious. She believed Marsha had been murdered, and she made that belief known to anyone who would listen. She gave interviews. She interrupted panels. She protested. She criticized the LGBTQ organizations and Pride committees that stayed silent about Marsha’s death. To Sylvia, this silence was unforgivable. Marsha had given her life to the community, and the community had looked the other way.

Over the years, Sylvia continued to speak Marsha’s name in every space she entered. She talked about her joy, her struggles, her generosity, and her brilliance. She reminded people that Marsha had been a Black trans woman who lived in poverty, did sex work, and faced constant violence. She refused to let the public rewrite Marsha’s story into something easier to digest.

Even in her final years, Sylvia kept fighting to get Marsha’s death reexamined. She believed that justice for Marsha was tied to justice for all the trans people whose lives had been taken and ignored. Though the police did not reopen the case while Sylvia was alive, her persistence helped others keep pushing. In 2012, twenty years after Marsha’s death, the NYPD finally reopened the investigation as a possible homicide. That decision was made in large part because of Sylvia’s refusal to stop asking questions.

Sylvia’s loyalty was not just personal. It was political. She understood that honoring Marsha’s life meant demanding justice, not just offering tributes. She did not want memorials filled with platitudes. She wanted real answers, real change, and real care for the people Marsha loved.

Even when the world moved on, Sylvia never did. She never stopped saying Marsha’s name. She never stopped telling the truth.

A Legacy of Truth, Not Myth

Today we remember Sylvia Rivera, born on July 2, 1951. A revolutionary, a street queen, a survivor, and one of the loudest voices our movement has ever had.

Too often, people reduce her to a quick line in a Pride timeline. They talk about her being at Stonewall, and then they stop. But Sylvia Rivera was so much more than a moment. She was a lifetime of fire, survival, and truth.

Sylvia was not a myth. She was a real person who felt pain, grief, joy, and betrayal. She faced police violence. She was unhoused for years. She lost friends. She struggled with addiction and depression. And through all of that, she kept showing up. She fought for trans people, for people of color, for sex workers, for poor and unhoused youth. She fought even when the people around her tried to silence her or push her aside.

She spoke when it was uncomfortable. She protested when it was inconvenient. She reminded people that queer liberation must include those most at risk or it means nothing at all. She did not fight for progress that left people behind.

When people erased trans people from legislation, she showed up and shouted until someone listened. When her best friend Marsha P. Johnson was found dead in the Hudson River and the case was dismissed, Sylvia kept asking questions. When Pride celebrations tried to push trans people out, she forced her way on stage. She never gave up. Not on Marsha. Not on the movement. Not on the people the world tried hardest to forget.

Her life was not easy. Her story is not tidy. But her legacy is one of persistence. She reminded us that queer history is not just parades and policy wins. It is survival. It is rage. It is chosen family. It is refusing to go quietly.

If we are going to remember Sylvia today, we owe her more than a quote or a rainbow-colored post. We owe her the truth. And we owe her action.

Support trans people. Listen to them. Defend them. Make space for them to lead. Speak up even when it’s hard. That is how we honor Sylvia Rivera.

Happy birthday, Sylvia. We’re still fighting.

Sources Cited

- Rivera, Sylvia. Queens in Exile, the Forgotten Ones, in GenderQueer: Voices from Beyond the Sexual Binary, edited by Joan Nestle, Clare Howell, and Riki Wilchins, Alyson Books, 2002.

- https://jackofall.art/wiki/wiki-index/queers-of-history/sylvia-rivera/

- Sylvia Rivera Law Project. “About Sylvia Rivera.” https://srlp.org/about

- Feinberg, Leslie. “Street Transvestite Action Revolutionaries: Survival, Revolt, and Queer History.” Workers World, July 24, 2002.

- Shepard, Benjamin Heim (2002). “Amanda Milan and The Rebirth of Street Trans Activist Revolutionaries”. From ACT UP to the WTO: Urban Protest and Community Building in the Era of Globalization. Verso. pp. 156–63. ISBN 1-85984-356-5.

- Stryker, Susan. Transgender History, Seal Press, 2008.

- Gossett, Reina, and Tourmaline. “Happy Birthday Sylvia Rivera.” The Nation, July 2, 2013.

- Stone, Andrea. “It’s Still Not Easy Being Sylvia Rivera.” Washington Blade, May 2001.

- Carter, David. Stonewall: The Riots That Sparked the Gay Revolution, St. Martin’s Press, 2004.

- Gan, Jessi, ed. The Sylvia Rivera Reader, Vellum Books, 2007.

- The Death and Life of Marsha P. Johnson. Directed by David France, Netflix, 2017.

- Sylvia Rivera’s “Y’all Better Quiet Down” speech, Christopher Street Liberation Day Rally, 1973. Video archived by DIVA TV and available via YouTube and the Lesbian Herstory Archives.

- Rivera, Sylvia, interview by Randy Wicker. Star People Are Beautiful People, 1998. Audio and transcripts available through the LGBT Community Center National History Archive (New York).

- Drag March Archive, NYC Pride Oral Histories Collection. New York Public Library Digital Collections.

- Gossett, Reina. “Sylvia and Marsha Are Still Watching.” Truthout, June 25, 2017.

- Spade, Dean. Normal Life: Administrative Violence, Critical Trans Politics, and the Limits of Law, South End Press, 2011.

- NYC Anti-Violence Project. “Remembering Sylvia Rivera.” https://avp.org

- The Reopening of the Marsha P. Johnson Case (2012), reported by The Guardian, New York Times, and Rolling Stone archives.

Leave a Reply